This is where the list of government advisory board members will go. For now, here are the results of a recent brainstorming session between Steve Caya, Infrastructure Program Chair, Rob Fischer, Governance Program Chair, and Peter Rafferty, with UW-Madison.

Structure & Management

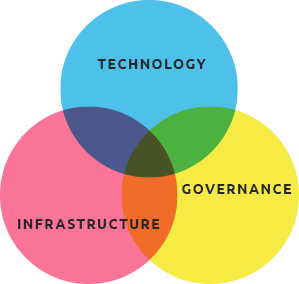

The governance structure of the AVPG is designed to enable smooth management and coordination, as well as to minimize common problems imposed by bureaucratic structures. The Joint Program Management Board consists of the coordinators of the three programs (technology, infrastructure, and governance). It is responsible for overall management, communication with the Executive Committee and other relevant stakeholders, and steering and monitoring research progress. The Joint Program Steering Committee, comprised of one representative from each of the current 11 full participants, decides on the admission of new partners, the integration of new research topics, and the strategic positioning of the research framework.

Close communication with city, county, state and federal authorities is a special focus, as are dialogues with the scientific community and with industry. The goal is to maximize synergy and to keep research strategy aligned with the real-life needs of communities and the economy. A Government Advisory Board has been established to ensure mutual knowledge transfer between research and government authorities. Its major aim is to initiate the transfer of new scientific findings, methods or tools into communities – and in return, provide feedback on their usability in practice.

The strategic management process includes regular thematic meetings and smaller events throughout the year, as well as two large annual workshops.

Working Groups Intro

Following are brief summaries of our initiatives.

Program on AV Governance

Focuses on policy, standards, public acceptance, certification, and developing a regulatory framework for AV technology, AV infrastructure, and the interaction between the two.

Program on AV Infrastructure

Takes an integrated approach towards understanding the interaction between AVs and smart infrastructure, including connected data, basemapping, and exchange protocols.

Program on AV Technology

Concentrates on the development of full suite of test environments for the safe evaluation and deployment of vehicles, sensors, hardware, software, and other technologies.

About Section – Intro Text

The mission of the Wisconsin AV Proving Grounds (AVPG) is to provide a path to public road evaluation by contributing to the safe and rapid advancement of automated vehicle development and deployment, and providing a full suite of test environments, coupled with research, open data, and stakeholder communication. Our team’s philosophy holds paramount safety, followed by best practice tenets of security and open data. Without these fundamental elements, we recognize it makes little difference what our readiness is or what research and development objectives may be.

New Mobility Lab

“Algorithm Aversion” and Scary Headlines

If it bleeds, it leads.

That’s the long-accepted dictum of how a news organization makes its biggest profit margin. News outlets provide an essential public service, but they must survive as businesses as well. Psychology Today noted this trend, saying that “news is a money-making industry, one that doesn’t always make the goal to report the facts accurately.”

Perhaps that’s why the Washington Post’s science section recently ran an article — the meat of which ended up being an exploration of why public fears of autonomous vehicles (AVs) are irrational — under the headline “Will the Public Accept the Fatal Mistakes of Self-Driving Cars?”

The article explored the idea of “algorithm aversion,” which, according to the Post and its sources, is the idea that “people are … more inclined to forgive mistakes by humans than machines.” The story cites public anxieties about refrigerators in the 1920s as a parallel example to current concerns about AVs, noting that “although scientists understood that cold storage could cut down on food-borne illnesses, reports of refrigeration equipment catching fire or leaking toxic gas made the public wary.”

All true, and a pertinent parallel. So why did the article need to begin with the line “How many people could self-driving cars kill before we would no longer tolerate them?” It might grab a reader’s attention, but the attention-grabbing part essentially represents the direct opposite of what the piece is about. This question is discarded and never addressed as the article proceeds. What purpose does it serve other than to stoke fear and get clicks?

Other recent articles in the pages of the Post follow this trend. When Uber rolled out its self-driving test back in September, the paper covered it. Buried in the article were some important facts: in the seventh paragraph, the writer mentioned that the vehicles “will have two trained safety drivers on each ride.” The twentieth paragraph — third from the bottom — briefly described Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto’s first ride in one of the Uber vehicles, of which he said “There was no time I was fearful or worried … I’m more worried when I’m on the road with an 18-year-old who is learning how to drive.”

That all sounds pretty good — so why did that article need the headline “Why Uber is Turning The Streets of a U.S. City into its Laboratory”? Or, in another article, why refer to voluntary Uber AV passengers as “guinea pigs”? A whole city reduced to an experimental lab? Humans as powerless and expendable as test-subject “guinea pigs”? Sounds positively dystopian. But, to anyone that knows about AV tech, it also sounds ludicrous and dramatically overstated.

Elon Musk weighed in on this issue back in October, saying “if, in writing some article that’s negative, you effectively dissuade people from using an autonomous vehicle, you’re killing people. Next question.” That’s a big statement — but unfortunately, it’s correct.

The fact of the matter is that AVs promise a level of safety that is currently impossible in our world of error-prone human drivers. The Post has quoted quite a few experts in many articles to that effect. But in order to address the logical fallacy of “algorithm aversion,” do they really need to sell the story using attention-grabbing headlines and scare quotes? The stakes are too high to be using frightening language.

Because the real “bleeding” that should “lead” are facts that, while far more dramatic than the material being covered in the AV realm, are perhaps not “news”, since they’ve been known for many years now. Each year, over 35,000 people die in car accidents. A full third of these come from intoxicated drivers. Another third are the result of reckless speeding. Distracted drivers represent another twelve percent. Human error is the cause of 94% of auto-related deaths. And across all modes of transport, these automobile deaths represent 95% of total fatalities, according to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. And perhaps one reason the total number of airplane and watercraft deaths are in the three-digit range instead of deca-thousands is that each relies on some degree of automation to reduce human error.

If the Washington Post is actually concerned about safety, perhaps it should start covering the 92 people killed every day in this country as a result of human error behind the wheel. They wouldn’t even need clever turns of phrase or headlines that don’t correspond to the information below them: the number itself is scary enough on its own.

Apparently “algorithm aversion” leads us to forgive human error more than we do machine error. But does that make it right?

Rob Fischer is President of GTiMA and a senior advisor to Mandli Communications’ strategy team. GTiMA and Mandli Communications are both proud partners of the Wisconsin Autonomous Vehicle Proving Ground.

Follow Rob on Twitter (@Robfischeris) and Linkedin.

Choosing How to Use Our Land

Next time you’re heading out of a big shopping center or a mall, scanning the endless sea of cars and trying to remember where you parked, take a moment to picture something completely different: a narrow drop-off/pick up lane, and beyond it, a tranquil, leafy park.

For now, you’re stuck with the parking lot. But that could change – this is a story about how we, as a community, choose to use our land.

A 2014 study of six cities conducted by UConn, in partnership with the State Smart Transportation Initiative, showed that “when measuring the amount of space given to parking … tax revenues for that real estate tend to be much lower than for other types of development.”

There’s one simple reason for that. Each and every parking spot in a city is taking up space that otherwise could be occupied by business, homes, schools. The study puts this in staggering economic terms. In Hartford, Conn., whose zeal for parking lot growth is about on par with the average American city, every individual parking space represents $1,200 lost yearly in potential tax revenue.

The total cost of parking spaces to Hartford? $50 million per year. This in a city where all downtown real estate brings in $75 million in municipal revenues. Imagine what cities would be able to do with an infusion of 66% extra revenue, if only all those parking spaces weren’t necessary.

Making matters worse, car-dependent communities devote more land to parking than you might expect. A 2007 Purdue study found that “the total area devoted to parking in a midsize Midwestern county … outnumbered resident drivers 3-to-1.” That’s right — in an average county, for every car, whether it’s on the road or not, there are three parking spots out there waiting for it. A Planetizen analysis of the Purdue study, among other studies, points out that “a city must devote between 2,000 and 4,000 square feet per automobile.”

When that’s all tallied up, Planitzen writer Todd Litman says, land used for parking “exceeds the amount of land devoted to housing per capita for moderate to high development densities … and is far more land than most urban neighborhoods devote to public parks.”

Of course, if we slashed the amount of land devoted to parking in cities, we’d simply be creating massive congestion problems as people circled blocks looking for somewhere to park. The surprising amount of waste imposed by parking lots is one of many burdens on society imposed by car culture.

And this is yet another externality that AVs promise to offset. With the advent of AV tech, and its steady evolution over the next decade or two, the need for parking lots will decrease dramatically. Experts agree that AVs will eventually be safe enough to be trusted to park themselves in designated lots — in much tighter confines, without the need for people to enter or exit their cars upon parking — a few miles outside of a city after dropping you off at an area close to the entrance of the mall. When you’re ready to leave, you’d simply summon it with your smartphone and it would dutifully return to carry you to your next destination.

This advance couldn’t come at a more opportune time. The UN recently estimated that by 2050, an additional 2.5 billion people will be living in urban centers across the globe. Under the current circumstances, if just one billion of those people drive a car, that would necessitate three billion new parking spaces. This is obviously untenable, especially considering cities will need to add housing and infrastructure to fit all the newcomers.

So while hunting for your car in a gigantic parking lot in a shopping mall is annoying and visually unappealing, it’s just a tiny piece of a mounting global emergency. Luckily for us, the solution – to this, along with other crises imposed by car culture – is a top priority of tech researchers and car manufacturers across the globe. If AV tech is rolled out safely and responsibly, this sprawling predicament will soon become a thing of the past.

Rob Fischer is President of GTiMA and a senior advisor to Mandli Communications’ strategy team. GTiMA and Mandli Communications are both proud partners of the Wisconsin Autonomous Vehicle Proving Ground.

Follow Rob on Twitter (@Robfischeris) and Linkedin.